Most of what I learned about masculinity I learned from growing up in the Bible Belt

After clicking to create a “new post,” I couldn’t even start writing this without my eyes welling up with tears. This topic feels heavy and very personal, and it comes at a time when life feels so fraught. Nevertheless I won’t let it stop me from dropping some good memes, outlandish childhood stories, reflections on my growth, and continued dialogue about creating a healthier future of masculinity.

Since I started this Substack, the intention has largely been to address the harmful systems and conditioning I experienced when I was young and discuss the growth, change, and healing—through the lens of psychology—that has come from unlearning those systems and creating new, better ways of navigating through the world and relationships. And there’s arguably no system that’s done more harm than patriarchy. Yet there’s perhaps nothing I’m more passionate about, and nothing that has brought more healing and growth, then undefining and redefining masculinity.

Some of my essays, especially the early ones, dove into some childhood stories and learnings about masculinity and manhood. This one is a good start. Yet it seemed high time to share a more complete story of how the thread of masculinity and manhood has wove through my life, and discuss how it’s changed for me, and why I believe this is such an important moment in time to have conversations about masculinity. I kicked a masculinity series off in my last essay, in which I gave a lay of the patriarchal landscape and addressed what I consider a health crisis for men. I made a case for a more healthier brand of masculinity. In this essay I share more of my personal journey.

A Bible Belt childhood

While I’ve considered myself to be open, transparent, and vulnerable here and on social media for several years, there’s something that was a rather large part of my life that I’ve never talked about publicly. This is due in part because after it was no longer part of my life, I buried it, like I did many things. But that changed over the last year through therapy, journaling, and conversations with close friends. So here it is: Fundamental Christianity made up just about my entire personality until my late-twenties. In fact, for many years during my childhood and early adolescence, when people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, my response was, “Pastor”.

It feels good to finally write about this because while close friends are aware of my Christian upbringing, and it’s a theme that I’ve explored in therapy this year, it’s not something that I’ve talked about online at all. There are a lot of reasons for that, not the least of which is that there are parts of that life that were altogether shameful, difficult, and traumatic. Some of the worst things I’ve experienced have been from “Christians” who used the Bible to justify their abuses, while I myself said and did things in the name of Christianity that I’m not proud of. And frankly, for a long time, I didn’t have anything good to say about it, except that I liked the potlucks and the church marquees were funny.

But while Christianity may have been such a significant part of my upbringing, it doesn’t even remotely describe my life or who I am today. If you’d like a label or phrase to better understand my beliefs today, it’d be something like a spiritual agnostic. (Note that when I talk about Christianity henceforth, I’m really talking about white evangelical Christianity, which reflects my childhood and adolescence experiences and the primary lens I saw Christianity through.)

Like many of my stories, we have to go back further than just my childhood. We begin with the childhood of my parents, who actually met in a Baptist orphanage in North Carolina. Much of what they learned there, even down to things like how to set the table for dinner and how to fold shirts, was passed down to me as a child.

Whether it was teaching me something new or reminding me of how to do something, my mom would often begin with, “Back at the orphanage, this is how we would do it.” So much of what my mom did and how she moved through the world was rooted in the Bible and what she learned at the orphanage. Up until the day she passed, my mom wouldn’t miss a service at the Southern Baptist church she’d gone to for decades. She was our family’s modern-day saint. Obviously, Mother Teresa at that time was saint no. 1, but it was then like Billy Graham’s wife, Dolly Parton, and then my mom.

So as you might expect, the division of labor in our home, the roles, responsibilities, expectations, and so forth were rooted in a more literal interpretation of the Bible. Men were the “head of the household”, women should be “self-controlled and pure, busy at home, and subject to their husbands,” women must “submit to their husbands,” women should be “silent in churches,” and women should "ask their own husbands at home" to inquire about something. These words come straight from the New Testament Bible and they in part are reflective of what I witnessed in my childhood.

Looking back on it, it felt like my childhood was grooming me to be a Southern Baptist church leader or even a pastor. I was practically a deacon-in-training at our church (Deacons are leaders of the church who served under the pastor). I read the Bible from cover to cover multiple times, could recite Bible verses better than I could recite state capitals, was a youth usher, led children’s church and Christian sports camps, gave my tithe every Sunday from my allowance, and rarely missed church.

I would go onto be on our church’s youth puppet team (yes, seriously), play gospel songs on stage of the church on my banjo, be an officer of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, lead bible studies at school, and I even performed a Christian comedy routine once at our church’s variety show. Arguably the peak of my Christian existence came in college, the summer after my freshman year, when I lived in a Myrtle Beach motel room with 8 other guys from the Christian organization we were involved in. On Saturdays we’d walk up and down the beach telling people to repent and follow Jesus. I was what the Christian band DC Talk might’ve called a Jesus Freak.

As you might expect, one of the names I was often given as a child was “Goody Two Shoes”. It wasn’t often that I got out of line, but there was one standout story from my childhood, when our pastor had started preaching past noon on Sunday mornings. That can slide from time to time, but I’d evidently had enough, and had been getting hangry.

So I devised a plan to subtly ask for my old man’s watch when the service started, and then once the preacher started his sermon, I asked to go to the front row, giving my parents some made up reason like I wanted to listen more carefully. I quietly and relatively unassumingly made my way to the front row. Then when the clock struck 12, and the pastor showed no signs of winding down, I raised my hand, holding the watch as high as I could so that he, and everyone else in the church, knew that he’d gone over time. I don’t remember what my punishment was, but whatever it was, it made me not pull that stunt again.

For further context of the Southern Baptist denomination (which for reference is the largest Protestant denomination in the U.S.), I was 1 when the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) passed a resolution that prohibited women from serving as ministers. It was during my adolescence when the SBC boycotted Disney because the happiest place on earth was extending benefits to partners of its LGBTQ employees. It may come as no surprise then, that as NPR reports, the SBC came into being in the mid-1800s as the church of Southern slaveholders.

That’s just the start of the SBC in the news. According to The Guardian, a 2019 investigation by the Houston Chronicle and the San Antonio Express-News detailed how dozens of Southern Baptist churches had "knowingly hired sex offenders, silenced victims, neglected to fire sexually abusive leaders and declined to report cases to secular authorities, or even document them within their own organization.” There were 700 victims in the investigation.

I feel like my childhood, and more specifically, our house, was a microcosm of the Southern Baptist Convention and Christian fundamentalism in America. There were very defined and specific roles divided along gender lines. I’ve previously written about the invisible labor of women, and the acknowledgement I’ve made as I’ve gotten older about the invisible labor of my mom. Her two days off were Sundays and Mondays. On Sundays after church we would often have a mini Thanksgiving-sized lunch, which including the clean-up, took my mom at least three hours of work. On Mondays, she’d start cleaning the house when I woke up for school around 7, and she wouldn’t be finished with everything until well after dinner at 9 or 10 p.m.

As for me, I probably didn’t do laundry until I went to college, and never remember seeing my old man do it. Neither of us ever cleaned. Neither of us cooked, except when he would occasionally grill or make dinner on special occasions. Our responsibilities included mowing the yard, car maintenance, fixing things around the house, and fishing—you know, men’s jobs. My mom waited on my old man and I hand and foot, and whether it was conscious or not, I took advantage of it. Yet within the context of my childhood and the culture I lived in, it seemed completely normal. That’s a problem to me because of how it reinforced patriarchy, sexism, and gender roles.

I can’t tell you how often some of the words I quoted a few paragraphs up from the Bible were used to reinforce gender roles. Often a chore or a request to do something was followed by a biblical line about the man as the head of the household or an idiom about “cleanliness being next to godliness.” Yet it was actually my mom who was often reinforcing this.

I share all this in part for context and insight into my upbringing and how it shaped my perceptions of gender roles and experience as a young boy and man. There’s so much of my upbringing, like the fact that I never did my laundry until college, and that my mom waited on my old man and I as if she was our servant, that was so patriarchal and disempowering. But while this describes my childhood and adolescence of the 1980s and 1990s, it’s very reflective of the patriarchy, gender roles, and inequality that’s alive and well both in America and around the world.

A 2023 study by Equimundo found that nearly 60% of millennial men (between 31-37) surveyed indicated that "men should really be the ones to bring money home to provide for their families, not women."

I’ll end this section with a Taylor Tomlinson bit that just about sums up what my resentment toward Christianity was like in my 30s.

Patriarchy and the Bible

This isn’t a Christianity think piece as much as it’s a patriarchy think piece through the lens of my Christian upbringing. While a portrait of my childhood and upbringing has likely formed for readers who have been here for a while, I hope that this essay colors in some details that have been missing. My intention isn’t to denounce evangelical Christianity and/or belittle the experiences or beliefs of Christians, though that may be how this all comes across to Christians. Because I agree with what Kristin Kobes Du Mez writes in Jesus and John Wayne, “There are also expressions of the Christian faith—and of evangelical Christianity—that have disrupted the status quo and challenged systems of privilege and power.”

In the sentence before that, however, De Mez wrote, “Across two millennia of Christian history—and within the history of evangelicalism itself—there is ample precedent for sexism, racism, xenophobia, violence, and imperial designs.” Patriarchy, sexism, inequality, racism, and abuse in a variety of different ways was very representative of the Christianity I experienced in my childhood and adolescence across many different churches, denominations, communities, and organizations.

Yet I’m grateful and encouraged when I see Christians and Christian leaders speaking truth to power, abuse, and patriarchy. It took courage for the Right Rev. Mariann Budde, during her sermon at the inaugural prayer service, to make a plea to President Trump to have mercy on immigrants and gay, lesbian, and transgender children who fear for their lives. Nevertheless, the attacks on LGBTQ+ people and their rights by the Trump administration continues. It’s no surprise then that despite the stark contrasts between the words and actions of Jesus and Donald Trump, that multiple surveys illustrate that approximately 8 out of 10 evangelical Christians support him.

My intention therefore isn’t to slay Christianity, but it’s very much to slay patriarchy and challenge those systems that prop up and perpetuate it. And considering my upbringing, I can’t talk about patriarchy in America without talking about the Bible and Christianity.

Frederick Joseph, in his book Patriarchy Blues, seems to come the closest to illustrating my thoughts about the relationship between Christianity and patriarchy. Here’s what Joseph writes:

I can't speak to what the Bible was intended to do, that knowledge is buried with its architects. But I do believe the text wasn't meant to be oppressive, but rather to be a body of work that speaks to liberation and morality. In fact, Christianity began as prophetic opposition to oppressive social and political systems of its time. But "morality" and "liberation" are both relative terms, and while the intent of Christianity and its doctrine have been rooted in liberation, the vantage point of how to build upon this intention solely derives from men's views and beliefs. —Frederick Joseph, Patriarchy Blues

Joseph writes that "the hierarchal structures established by both patriarchal culture and Christian doctrine have combined to create inequality and oppression." Joseph alluded to numerous examples from the Bible of “overtly canonized patriarchy,” including 1 Corinthians 11:4-9. It ends with, “But a man should not cover his head, because he is made like God and is God’s glory. But a woman is man’s glory. The man did not come from a woman. The woman came from man. And man was not made for a woman. Woman was made for man.”

I’m not here to debate whether the chicken came before the egg, the egg before the chicken, or patriarchy before Christianity. But patriarchy and Christianity, and more broadly religion, have long been in the same bed together. "Patriarchal religions, like Judaism and Christianity, established and upheld the 'man's world,’" wrote Barbara G. Walker in The Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets. And this is what Frederick Joseph echos in Patriarchy Blues.

Not only was the text of the Bible written by men, but the reading and interpretation has also historically been a role designated primarily to men, and more times than not, cisgender heterosexual white men. This has allowed them to preach and teach a word from the perspective of someone with an agenda often aimed at further bigotry and personal gain.

Again, this is not to say that the nature of Christianity is inherently oppressive, but rather that throughout history, many of of the people who have had power within Christianity have knowingly or unknowingly furthered and upheld oppressive ideologies and structures. Especially those rooted in white colonial patriarchy. There is a conscious effort in many spaces to lean into the most radically liberating aspects of Christianity, but this work is moot without also navigating accountability and accepting the truth that Christian beliefs have constructed and insulated much of the patriarchal oppression many people face.”— Frederick Joseph, Patriarchy Blues

Many Christians, churches, and Christian organizations have distanced themselves from the term “patriarchy.” and who could blame them? Patriarchy’s PR agency is winning no “Public Relations Campaign” of the year awards. Instead, recent years have seen many churches and church leaders gravitate to the the term “complementarianism,” which has been used to describe different, but “complementary” gender roles within marriage, relationships, and churches. But this just feels like repackaged patriarchy, like calling a Cybertruck a truck. And on that note, here’s a Ken interlude feat. the patriarchy.

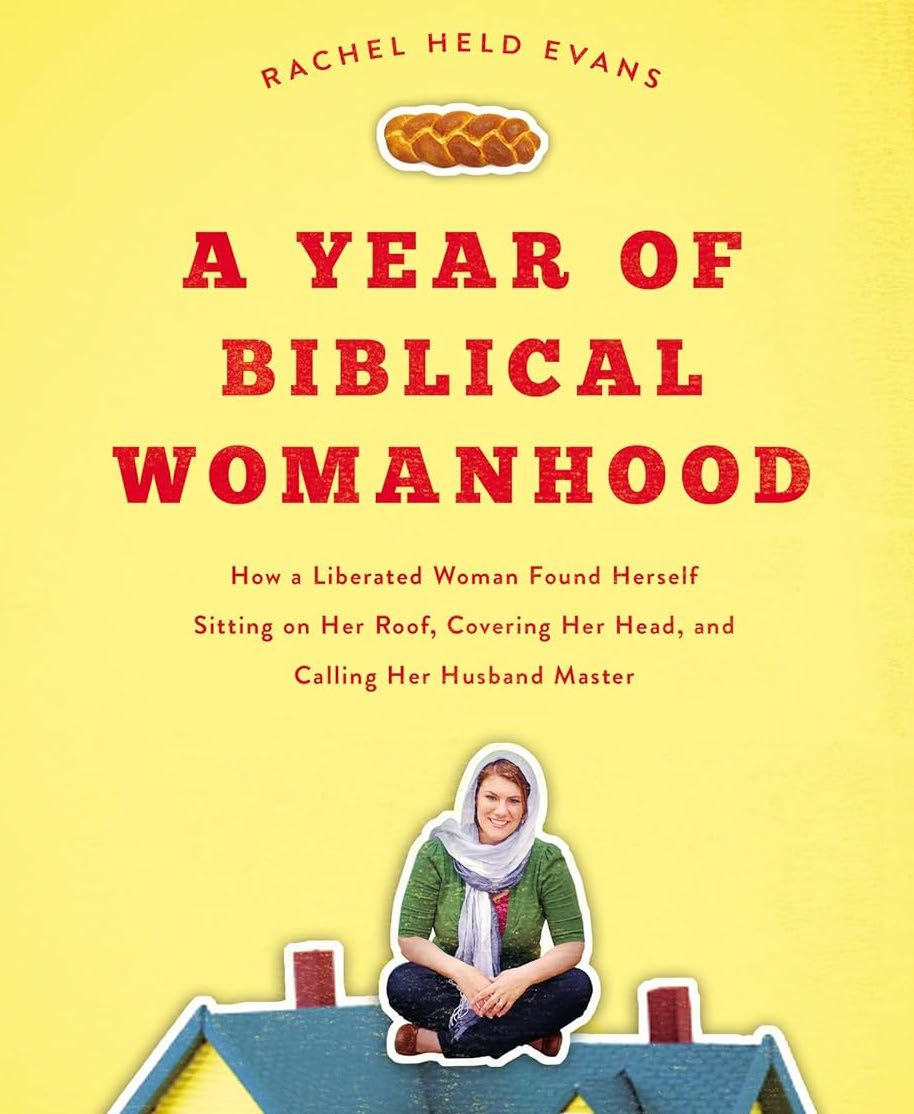

Christian columnist and author Rachel Held Evans wrote, “When a man with no biblical training whatsoever is considered more qualified to teach than a woman with a PhD in theology or a woman whose work in New Testament scholarship is renowned the world over, we are not seeing complementariaism at work, but patriarchy.” Evans continues, “Complementarianism isn’t working—in marriages and in church leadership— because it’s not actually complementarianism; it’s patriarchy.”

Rachel Held Evans, who tragically passed away a few years ago, is one of many Christian women who have been challenging Christianity’s brand of patriarchy. She wrote a punchy, humorous book, called A Year of Biblical Womanhood, in which she vowed to follow as many of the Bible's instructions for women as possible for a year. This included remaining silent in church, camping out in her yard during her period, submitting to her husband, and calling her husband "master." As you might imagine, it didn’t go over well with many people.

Yet Evans reminds readers that if there’s something you’re looking for in the Bible—be it verses supporting oppression, verses abolishing oppression, verses uplifting women, and verses oppressing women—then you’ll find it. She writes, “If you want to do violence in this world, you will always find the weapons. If you want to heal, you will always find the balm.”

Other books are more academic in nature, like Beth Allison Barr's The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. The book description begins with “It is time for Christian patriarchy to end.” As women have challenged patriarchy in contemporary society, like in media, Hollywood, and workplaces, so are women doing so within Christianity. She minces no words when she writes the following.

“Patriarchy walks hand in hand with racism, and it always has. The same biblical passages used to declare black people unequal are used to declare women unfit for leadership. Patriarchy and racism are "interlocking structures of oppression" Isn't it time we get rid of both?” ― Beth Allison Barr, The Making of Biblical Womanhood

The fact is that despite the advances and progress in America, and more broadly the world, equality continues to lag behind, and we continue to fail women. According to focus2030.org, no country has achieved gender equality. Gender equality has deteriorated in 18 countries, while one in three countries have made no progress since 2015. According to a report published by UN Women, it could take about 300 years to reach gender equality at the current rate we’re going.

And don’t even get me started on America’s treatment of women. The last few years have been devastating to women’s rights and access to things like healthcare, abortion, and other services in America. As this NPR article illustrates, many of the states with the most restrictive abortion laws tend to have less health care access and financial support, and worse outcomes. It’s even worse for women who aren’t white.

In 2023, as NBC News reports, the U.S. ranked 43rd on the gender parity index, which was a drop in 16 slots. Pew Research Center has shared sats on some of the gains in America, yet the gaps can’t be ignored. The gender pay gap in America, for example, has hardly changed since I was a teenager. The last few years it’s been between 80 to 83 cents for every dollar that men make. It was 80 cents in 2002, according to Pew. The needle is moving in the wrong direction.

As I wrote in my last essay, many of the happiest and healthiest countries, and those with the highest life expectancy, are also some of the most equal countries. You can read more about that here and here. Perhaps then—and I know this may be a crazy, revolutionary concept—what if the energy, fervor, and money we put into banning books and debating transgender athletes was put into equality? It’s a novel concept.

My Adolescent Experience of Masculinity

Above, I wrote about my Southern Baptist upbringing, which paints just part of the picture of my childhood and adolescence. Now I want to fill in more details about my adolescent experience, and more specifically, I want to talk about the models of masculinity I had, and how that shaped my experience of boyhood and manhood.

As I was growing up, whether it was spoken or unspoken, it was obvious that there were certain roles and characteristics I was supposed to embody, and certain activities I was supposed to spend time doing. Anything less wasn’t becoming of a man.

Men took care of the car and house (though they didn’t clean), they fixed what was broken, they made major purchasing decisions (women as a whole were only able to get credit cards on their own in the mid 1970s), they took on leadership positions, they planned and organized travel, they were the primary drivers, they were the breadwinner, they protected, they camped, they fished, they hunted. I admit that the latter didn’t go quite so well, since one of the first times I shot a gun, I shot myself in the finger with a BB and had to be taken to the emergency room to have it removed.

But along with what I learned men were supposed to do, I also learned what boys and men were not supposed to do. Blue is for boys, pink is for girls. Boys and men could wear hats, but they should be baseball or cowboy hats, and definitely not a beret or fedora unless you were dressing up as a gangster for Halloween (Yes, I dressed up as Dick Tracy in elementary school). Boys could play with G.I. Joe action figures but not Barbie. Boys should play contact sports like football, yet had to play them a certain way; otherwise you could be made fun of for running or throwing “like a girl.” Boys and men could play music, but only certain instruments, and they shouldn’t play in the marching band.

Boys and men could dance, but not try out for the dance team. Men should cheer for sports teams, but not be cheerleaders (I would like to apologize to the male cheerleaders in college who I and my Christian friends made fun of). Men could show emotions, but only a limited number of emotions like anger, and they can never cry. Men could help others but shouldn’t ask for help, and they shouldn’t have caring or helping jobs like nursing. Men should protect women, yet could say and do whatever they wanted to their “woman” without repercussions. Men could show affection by high fives or fist bumps, but not by hugging or holding hands. If someone hits you, you hit them back, because it’s an “eye for an eye”. Ask God for forgiveness, but don’t say you’re sorry to others.

Yet that’s nothing compared to the expectations, norms, and roles expected of women. I couldn’t even begin to speak to the experience, so I’ll just let America Ferrera’s speech from Barbie do the talking.

These were the spoken and unspoken rules of my childhood and adolescence. Hypermasculinity was like the air I breathed. I can’t tell you how often I was told as a child that I threw or ran like a girl, even by male family members. I was told that I was a “sissy” if I wanted to play in the marching band. I was asked numerous times if I was “gay” because I didn’t have a girlfriend in high school. And there was a litany of male tasks, like using a table saw, that I was “supposed” to be competent at, but couldn’t quite grasp as a child. When I made a mistake, I would then be shamed about it, and on the occasions that I cried for being yelled at or swore at, I’d get sent off for crying. The latter arguably had the most significant effect.

Yet in almost the same moment that I was being victimized by modern-day, unhealthy masculinity I was also perpetuating it. There’s one story that stands out from high school. I experienced teasing, bullying, and downright meanness, especially about my weight and dating. In this particular instance, however, I was the one being mean.

It was around ninth grade, while some classmates and I were gathered around a book cart in the library. My classmates were egging me on to ask out one of our new classmates, who I’ll call Nancy, who’d recently moved to the area. I didn't know much about her except she was artsy, stylish, and believed in something that I knew little about, called Taoism. She was in the general direction of where we were standing, and caught wind of the conversation. Then in front of a group of people, she flat out asked me if I’d go on a date with her. I immediately froze. “I only date Christians,” I sarcastically blurted out, chuckling as I said it. I immediately regretted it and felt disgusted, and all that much more when I saw how much it hurt her.

Masculinity, or rather an unhealthy model of masculinity, was on display everywhere around me throughout my childhood and adolescence. My old man was emotionally, verbally, and in a few instances, physically abusive. One of my basketball coaches went to prison for a ghastly number of child sexual abuse charges. And one of the organizations my church in high school was involved with shut down just a few years after a documentary that implied it was a cult. It was one of the largest youth ministries in America.

I witnessed how women in my life were mistreated, cheated on, abused, and more from men who’d made oaths to protect them. There was a trail of destruction left by white men in my life, and I saw how their behavior not only came with few consequences, but was often rewarded. This version of masculinity that I witnessed and that was modeled to me is why I believe that I ultimately started to repel and resist so much of masculinity at a young age. I methodically, slowly, and tacitly started suppressing and cutting off parts of myself. I didn’t want to be cool, accepted, strong, and masculine if it meant that I had to be mean, arrogant, patronizing, demanding, sexist, and aggressive. I didn’t see any middle ground.

A lot of things changed in the years that followed. I let a lot of my male friendships fall to the side. Most of the close friendships I made were with women. And I quit things that I’d previously enjoyed, like camping, fishing, and some sports that were tied to certain abusive male relationships. It seems then like I would have softened more, and that after repelling certain masculine characteristics, that I would’ve leaned into feminine characteristics like vulnerability, authenticity, intuition, emotional awareness, and communicativeness. However, that wasn’t the case. In fact after what I experienced for crying as a child, I went some 7-10 years without crying.

Nevertheless, there were some characteristics often associated as feminine, like compassion and patience, that I developed more of. But it’s like I became this shell of a person, because I became so intent on suppressing certain human experiences and emotions because of the behaviors I’d associated with them. I became this more passive, distrusting, stoic, detached, timid version of myself. I thought that if I just numbed the bad stuff, that I would invite more light and good in my world and be impervious to the effects of traditional masculinity that I witnessed. But as Brené Brown writes in The Gifts Of Imperfection, “We cannot selectively numb emotions. Numb the dark and you numb the light.”

“Learning to wear a mask (that word already embedded in the term “masculinity”) is the first lesson in patriarchal masculinity that a boy learns. He learns that his core feelings cannot be expressed if they do not conform to the acceptable behaviors sexism defines as male. Asked to give up the true self in order to realize the patriarchal ideal, boys learn self-betrayal early and are rewarded for these acts of soul murder.” ― bell hooks, The Will to Change

Life hit the fan in my mid-twenties. Between the age of 25 to 27 my father had passed away, I got into a relationship I had no business getting into, that relationship became a marriage, all of my original groomsmen (who I’d gone to college and been involved in a Christian organization with) boycotted my wedding because my fiancee and I moved in together before we were married, I lost my dream job, I had a hard time finding work, I incurred thousands of dollars of debt, and then went through a divorce that I’d caused by dishonesty about the debt. Yet I’ll own the mistakes I made and admit that I made a lot of missteps, and also hurt a lot of people by trying to live up to this masculine ideal while simultaneously abandoning myself.

I’d spent so much of my adolescence trying to resist modern-day masculinity, and yet in my late-twenties it’s like I’d become the type of man I swore I wouldn’t be. I felt immense shame, was depressed, and literally made myself sick with anxiety.

In hindsight, it seems as if it was something of an invitation from the universe. Call it an inciting incident, the beginning of my hero’s journey, Saturn’s return, or whatever you want to call it. But if it’s like the universe was giving me a collect call, I wasn’t ready to accept it yet. Instead, I spent the following years throwing myself into building a writing career, traveling, and moving from place to place, and largely avoiding connection to myself and others. I was an impenetrable island. Brené Brown, in talking about what she describes as "Act Two" of the hero's journey, is when they try "Every way to solve the problem that does not require the hero’s vulnerability." That was me.

Addressing modern-day masculinity

I believe that we live in a time, both in America and around the world, when patriarchy, unhealthy masculinity, and other oppressive systems are on full display. The most recent U.S. election, and the after effects, make that evident. Yet I refuse to talk about patriarchy without addressing the systems, discussing the impacts for men, and exploring solutions. Because culturally, we’ve spent years talking about “toxic masculinity” and patriarchy without offering men solutions, hope, community, and connection.

While patriarchy gives the allure that it benefits men, it’s men who are both the victimizers and the victims who experience much of the destructive impacts. Simply put, men are in crisis, and that’s evident by the rates of loneliness, suicide, and more among men. I shared a lot of statistics in my last essay, which I won’t repeat here. But the stats are grave. This is a house built on sand. Patriarchal culture is destructive for everyone. No one benefits.

To me there seems to be this unspoken presumption that if we just cancel men or tell men to stop being so toxic, patriarchal, masculine, or whatever word you want to insert here, that patriarchy will just dissolve and men around the world will become better. That will no more happen than you can tell everyone to stop buying plastic bottles and assume that climate change will dissipate. I spent a lifetime trying to ignore, suppress, and do the opposite of patriarchal masculinity, and I still perpetuated it. So this can’t just be lip service or a game of the opposites where we just tell men to do the opposite.

Among the problems of addressing patriarchy are the consequences of even the smallest changes and deviations from traditional masculinity. For example, despite evidence that men have been painting their nails since 3500 BC, many boys and men, including professional athletes like Caleb Williams and Jared McCain, have been bullied for painting their nails. In the very few men’s pro sports leagues that have paid paternity leave, few men take it, and when they do, they’re often eviscerated, like when Daniel Murphy took 2 MLB games off in 2014 for his child’s birth.

And then there are the consequences when men start to deviate from masculine sexuality. Data scientist Seth Stephens‑Davidowitz uncovered some interesting data about believes and prejudices, including search engine data that wives are 10 times more likely to Google "Is my husband gay" than "is my husband depressed". What does it tell us when society is more concerned with someone else’s sexual orientation and sexuality than epidemics of depression, loneliness, and suicide?

I’m not sure there’s a recipe for this. However, I do want to say that one of the most important things for me was to throw a monkey wrench in the spokes. Once-in-a-lifetime pandemics and break-ups will do that. Because it made me stop and look at my life in ways that I hadn’t before.

I believe that for many men, and especially white men, they are so embedded in the white supremacist patriarchal engine, that they can’t even see the destructive effect it has on themselves, and let alone the effect it has on others. So understanding that system, the origins of it, and the cycle of abuse and trauma in my own family, and more broadly the world, was the first step. I had to put a mirror up to myself, my family, and my roots, and come face-to-face with the oppressive and dominator model that had rolled down generations. It didn’t matter how much I tried to resist it and how much of a kind and good person I tried to be, I couldn’t begin to understand the impacts of patriarchy, on myself and others, until I pulled back the curtain.

It’s been a journey of more than a decade, though the deep dive has been the last few years (This essay goes into much more details.). The inciting incident was in 2018, after a break-up, when I finally decided to go to therapy when I acknowledged that I couldn’t keep a relationship for more than 6 months. Up until then, I’d really never even thought that my upbringing may have created unhelpful and potentially harmful thought and behavior patterns. So began the great pause, and beginning to address the systems that I grew up in. With it came a great awakening that never came with 27 years of Christianity.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom.”—Viktor Frankl

This idea of pulling back the curtain on patriarchy is reflected in what I hear from many psychologists and authors. Terry Real, a couples therapist and founder of the Relational Life Institute, talks about how you can be in power or you can connected, but you can’t be both. Because as Terry says, within patriarchy, power is “power over” and not “power with”. So by definition, we’re breaking connection when we choose power over, which is central to patriarchy. Terry writes the following in an article on his website:

“In the one-up, one-down world of men, there’s no place for “same as,” and hence no platform for real intimacy. You’re either a winner or loser: dominator or dominated, grandiose or shame-filled. And you can’t be truly intimate from either the one-down (shame-filled, “feminine”) or the one-up (grandiose, “masculine”) position.” —Terry Real

In The Will to Change, bell hooks writes, “When culture is based on a dominator model, not only will it be violent, but it will frame all relationships as power struggles.” Patriarchy and this dominator model is the air we breathe. And when it doesn’t get addressed on individual, relational, and collective levels, it simply persists and continues to be perpetuated, because that’s the system that societies, cultures, and relationships are built on. America doesn’t run on Dunkin, it runs on patriarchy.

“Seeking to heal the wounds inflicted by patriarchy, we have to go to the source. We have to look at males directly, eye to eye, and speak the truth that the time has come for males to have a revolution of values. We cannot turn our hearts from boys and men, then ponder why the politics of war continues to shape our national policy and our intimate romantic lives.” ― bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

I want to end with a little bit of a personal anecdote. If holding myself accountable and doing an excavation of my family history, childhood, and patriarchal history laid the foundation for unlearning patriarchal masculinity, healing, and changing, then listening to the stories of women and reading female perspectives was like the cornerstone. There are a lot of people I owe a lot of thanks to, not the least of which include both therapists that I’ve worked with (and countless other therapists I’ve learned from), my sisters, several close female friends, and a couple of my longer relationships in the last seven years.

They’ve all taught me something, challenged my preconceptions, and inspired me. And in turn, they’ve compelled me to do my own work of empathizing with women, not overlooking the experience of women (and non-binary people), unlearning patriarchal thought and behavior patterns, and really listening to women. The 2016 election, MeToo movement, 2020 pandemic, and overturning of Roe v. Wade are certainly some of the major events that have made me take pause. But more than ever, I’m reminded of how important it is to listen to women. Believe women.

Where do we go from here?

I believe that this work for many men is like addiction recovery, which I wrote about in a recent essay. Because we’re dealing with systems that the world, culture, and people’s lives are essentially built on. And as the research suggests, there are consequences from deviating from these systems. So we first have to acknowledge these systems, and the history of them, and address the issues that they cause (and address our own personal histories). I believe that we then have to make resources, talk about incentives, build healthy masculine communities, and create new ways of moving forward.

Because for many men, there are no resources, communities, or solutions at the ready. One of the most inspiring things about the women’s movement over the years is how women have come together, been vulnerable, formed tighter relationships, created community, told their stories, written books, developed resources, and learned from one another. It’s so damn beautiful and gives me such hope. Yet for many men they have no friendships. As this Los Angeles Times article points out, 1 in 7 men have no close friends. None. That is heartbreaking. Yet I feel that deeply. I was 28 years old before I had my first close male friendship.

I see this changing some, but the growth has been marginal. A good example is the men’s self-help section at bookstores. Many bookstores don’t even have a section for men, and when they do, it’s typically a shelf at most. Many of the books about gender, relationships, and masculinity, like the beloved Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus, only perpetuate the division, sexism, and patriarchy. That’s not just my opinion, as some of the science would confirm this. Yet in recent years there’s been a steady increase of books—some of which I’ve quoted in this essay—that are undefining and redefining masculinity. I’m grateful for some of those books, which have been so impactful for me.

Nevertheless my point is that historically, there has been an absence of information and resources about healthy masculinity. A recent study, small as it may have been, speaks to this, as it highlights how struggling men are driven to incel groups.

I believe this absence of healthy models of masculinity, communities, and resources has provided a vacuum for repackaged, but unhealthy masculinity to enter. And young boys and men looking for inspiration, worth, and meaning have flocked in recent years to these really charismatic, confident, tell-it-like-it-is men who are selling this hypermasculinity that speaks to men’s egos and makes lots of promises, but ultimately underdelivers, disempowers everyone, and reinforces our white supremacist patriarchal culture.

Yet I can’t help but wonder if as a society we’ve spent so much time cancelling and calling men out, that we’ve missed opportunities to call men in. And make no mistake about it, many men want leadership, connection, community, and inspiration.

And I believe that many men will continue to find community and connection from men ill-equipped to lead as long as we continue to use terms like “toxic masculinity” and shame men and call them out rather than calling them in. I’ll echo what many researchers, including Brené Brown have said, that shaming is not an effective social justice tool. It alienates the very people we’re trying to build connection with, and I believe this is especially true for the group of people, namely men, who have grown up in a system (patriarchy) built on shame, fear, and control.

“To create loving men, we must love males. Loving maleness is different from praising and rewarding males for living up to sexist-defined notions of male identity. Caring about men because of what they do for us is not the same as loving males for simply being. When we love maleness, we extend our love whether males are performing or not. Performance is different from simply being. In patriarchal culture males are not allowed simply to be who they are and to glory in their unique identity. Their value is always determined by what they do. In an anti-patriarchal culture males do not have to prove their value and worth. They know from birth that simply being gives them value, the right to be cherished and loved.” ― bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

What now?

My tears just welled up with tears as I reflected on the last few years. And it’s taken every bit of a few years to address the patriarchy and unhealthy patterns I was perpetuating, explore generations of trauma perpetuated by men, and start stepping into a more healthy version of manhood and myself. It’s some of the hardest, yet most important, powerful work I’ve ever done. And to see, experience, and feel the results of that work, I’d do it over and over again for the rest of my life.

“Family dysfunction rolls down from generation to generation, like a fire in the woods, taking down everything in its path, until one person in one generation has the courage to turn & face the flames. That person brings peace to their ancestors and spares the children that follow.” — Terry Real

I believe in part that this is my life’s work. And I believe that to an extent it’s all of our work. Because if we want to mend division, have equality, build healthy relationships, and heal the planet, then we all have to acknowledge, address, unlearn, and heal the systems that have brought us here.

I believe that we’re seeing it to an extent. Many major publications, including The Atlantic and The New York Times, have written articles in recent months about the progress and growth of a healthier, most positive brand of masculinity. Musicians like Andy Grammar, Macklemore, and Dax are singing about it. It’s entered our homes through shows like Ted Lasso. And it’s even entering our workplaces and schools. In my own neighborhood in Portland, at Cleveland High School, there’s a healthy masculinity club that’s modeled after the work of one of my favorite organizations, A Call To Men. My friend Matt wrote about it for CNN.

This gives me a lot of hope. I imagine a future, when the air we breathe aren’t systems of patriarchy and inequality, but rather equality and love. I don’t believe that’s too much to ask for.

“What the world needs now is liberated men who have the qualities Silverstein cites, men who are 'empathetic and strong, autonomous and connected, responsible to self, to family and friends, to society, and capable of understanding how those responsibilities are, ultimately, inseparable.” ― bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

For more than half my life, Christianity, God, and the Bible were my North Star. To say to Christianity that “it’s me, not you,” feels like a helluva oversimplified way to put it. But the fact is that modern-day Christianity—in all its many forms—didn’t go far enough for me. Christianity, as well as other belief systems, went part of the way in shaping and informing my spirituality. Yet it wasn’t Christianity that I had to demand change from, but rather I had to demand change of myself. I had to address the systems I was given. I had to change the narrative. I had to redraw the map. And the redrawn map doesn’t include a path toward Christianity, or toward any one religious system.

Some may say that I was never filled with the Holy Spirit and a Christian to begin with. And that’s fine if they believe that. Maybe I never was a Christianity. What I believe in is the power of love, connection, goodness, healing, change, and wholeness, both in myself and others. I am living proof. And I’m far kinder, self-aware, connected, empathetic, gracious, healed, curious, and loving (and still becoming those things) in the years since then I was during the 27 years in the system of evangelical Christianity.

So what is my North Star now? What gives my life meaning? In a word, it’s love. To be hippy AF, it’s love for myself, people, planet, and as I said in the paragraph above, believing in the power of love, healing, connection, and a helluva lot of other beautiful things. The world that I want to live in is one in which love and liberation is in abundance. And I don’t believe that there’s liberation where patriarchy undergirds relationships and our ways of life.

In closing, I thought about and read a bunch of quotes that I love before writing this part, and the one that felt most alive, was this from Carl Jung: “The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.” This is my North Star. And it never ends.

"We are all in the process of becoming." — Audre Lorde

For your next dinner party

Earlier, I mentioned the resentment I had toward Christianity in my thirties. But it’s kind of like, take a number, Christianity, and get in line. What didn’t I have resentment toward? I’m by no means healed of resentment. But as I recently told my therapist, I’m finding myself and my history with evangelical Christianity at a place that’s more of a crossroads of where forgiveness and accountability meet. But in a way that’s like I got my eye on you.

This past year, as I’ve finally opened up about my religious upbringing and been able to put words to it, I’ve been compelled to listen to as many stories from other people who have been on or who are going on a deconstruction journey. I’ve been so inspired and moved, and I share all this in part, so I can connect with more people and have more conversations about this.

I have read and listened to a lot of people’s deconstruction stories, but one of the first that I listened to, from Rhett McLaughlin of Good Mythical Morning fame, has been one of the most impactful. Both Rhett and his co-host, Link Neal, grew up not far from where I grew up in North Carolina. They were deep in Christianity and Christian ministry for years until they both went on their own separate deconstruction journeys, which they first shared about on their podcast several years ago. Every year since they do an episode on spirituality and deconstruction, and their episodes have been so inspiring and thought-provoking. You can see the first one they recorded below.