Yes, Sober October is a thing. Yes, I’m here for it. And yes, of course I felt like I had to write about it since this week marks 18 months since my last drink. It’s been 20 months since I quit coffee (I’ve had caffeine in very small doses). And it’s been about 15 months since I had any weed. Approaching year 1 felt like a thing—there came a point where it’s like ok, I’m doing this, I’m going to go a year without a drink. And now that it’s been a year and a half, this just feels like life.

Beyond Sober October, and this marking 18 months off booze, it seemed like a very fitting time for me to dive more into what I’m learning, especially after recently completing my first semester of grad school for Arizona’s State’s Master’s of Science in Psychology program. (You can see my first essay about sobriety here from my one-year mark.)

While my degree doesn’t focus on addiction, it has come up in different ways in many of my classes. And it’s naturally spurred me onto do some of my own reading and research. It’s been so illuminating, yes in part from navigating my own journey here, but also as I’ve met others on their own sobriety journey, listened to their stories, and dove more into the science and research behind different substances, addiction, dopamine, trauma, and all the things. And so here I am, on my school break, and I’m reading about addiction and writing a Substack essay about it.

I want to begin by saying that one, I’m not a doctor, and I don’t yet have a degree in Psychology. This is not advice. This is primarily an essay of my own experience, with a few hot takes, and a sample of some of the research I’ve read. I’m neither here to judge you nor tell you what you should be eating, drinking, and doing with your life.

This has been my journey, has become my lifestyle, and are the choices that I’ve made and am making. There are no two stories that are alike when it comes to pontificating about alcohol, drugs, and the effect of these and other things. What’s more, you’ll find no shortage of stories from people who’ve lived hella long lives, and who credit a tipple for their long life. Just take a look at this one, this other one, and here’s another one featuring people over the age of 100 (actually all women) who have stood by their regular consumption of beer, wine, or booze. Damn, I’m envious.

However, among the most important decisions and lifestyle changes I’ve made, there are few that have been more important than my decision to cut out alcohol and caffeine. I in part mention alcohol and caffeine together, because for me, they were connected. Nevertheless, this topic of sobriety and addiction is wildly complex, challenging, polarizing, and dare I say one of the most significant issues of our time (especially considering that I’m from the country that declared war on drugs). And it’s also ripe with misinformation.

I want to touch on all of this. So without any further ado, let’s get into it.

The day I started thinking about addiction differently

If you’ve been here before, then you’ve likely read this story multiple times, but I’ll try to keep it brief(er). But about 20 months ago I was in my therapist’s office telling her about a conversation that I’d had with my former girlfriend. At the time of the conversation between my ex and I, we weren’t together, but had gotten together to talk through some learnings and reflections about our relationship. I was recounting this conversation to my therapist, and telling her my side of things, when my therapist stopped me, and said, “That’s codependent.” She was like, the behavior/conversation of yours that you’re describing is codependent.

My first reaction, which I didn’t express out loud, was something like wanting to yell, “YOU DON’T KNOW ME, I’M NOT CODEPENDENT.” But then after sitting with this for a moment I calmly responded to my therapist, “Wait, what? Ok, so what’s codependency then, because I must not completely know what it means.” And I didn’t.

I was mortified, and angry deep down. I’d been in therapy for 4 years, and had been deep-diving for months into family history, childhood trauma, and old thought/behavior patterns that had resurfaced. In the months since I’d never experienced such profound growth. How did I miss this? I thought I was done digging.

It’s kind of like (but not really at all) if I’d set out from Portland, Oregon to walk across America. And after days of walking, upon reaching a big, winding river that I assumed was the Mississippi, I instead discovered that it’s the Snake River, and I’ve only reached the Oregon/Idaho border. I felt like Elf finding out that his dad was on the naughty list, except I was the one on the naughty list.

I’ve talked about codependency ad nauseum, but I’ll give you the quick rundown. Psychologist Robert Subby, in describing codependency, writes that it is "An emotional, psychological and behavioral condition that develops as a result of an individual’s prolonged exposure to, and practice of, a set of oppressive rules -- rules which prevent the open expression of feeling as well as the direct discussion of personal as well as interpersonal problems."

I consider

one of the foremost experts on codependency, and I love how she defines and expresses codependency. Listen to her take here:I grew up in an abusive household. Therapists have made a strong case that one parent was immensely codependent while the other was narcissistic. So using Subby’s codependency description, I grew up in an environment with a “set of oppressive rules,” and rules that prevented “the open expression of feeling as well as the direct discussion of personal as well as interpersonal problems.” It’s like I inherited the system of my parents, who in part likely inherited it from their parents, since they were the children of parents who were alcoholics and abusers.

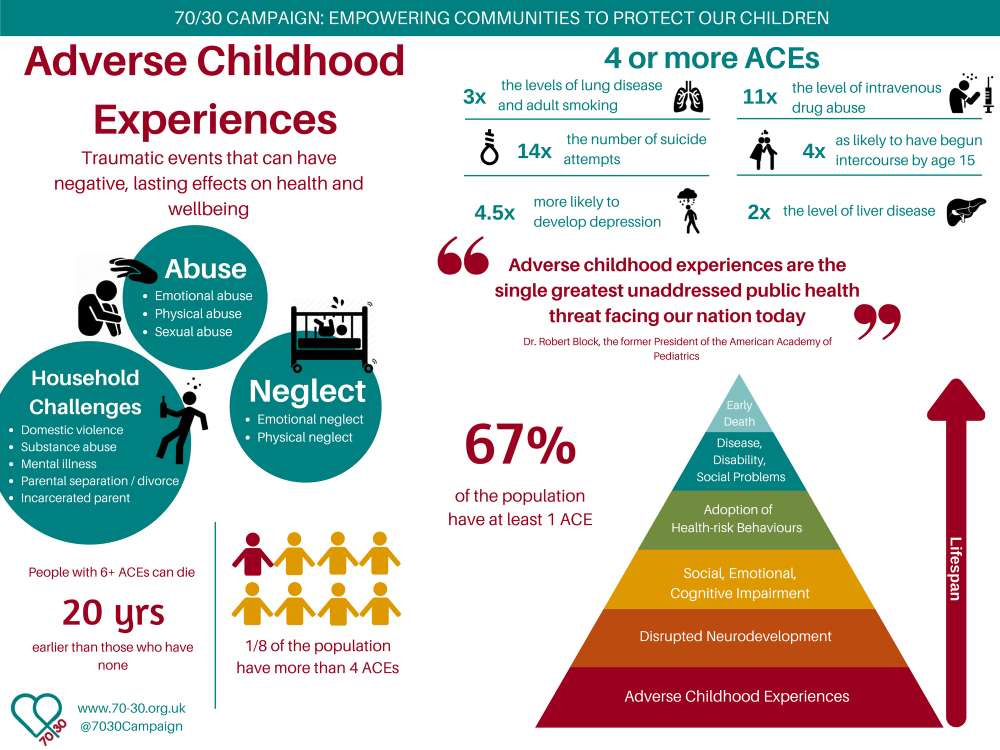

There may not have been alcohol or drugs in my childhood environment, but it was an environment ripe for developing addictions. I’ve previously talked about the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) questionnaire, which is a 10-question test that measures the trauma of your childhood. I only wish that as many people as possible could score a 0. Anything above that can have unhealthy consequences. According to one study, the higher the ACEs number, the higher the chance of heart disease, depression, PTSD, substance abuse, obesity, and other problems.

My score is about 4-5. According to the American Journal of Preventative Medicine, “Children who experience four or more ACEs are 7.4x as likely to suffer from alcoholism and 12.2x as likely to attempt suicide.” I am that statistic. What's more, my likelihood of heart disease, cancer, liver disease, and many other health risks are increased several fold compared to someone who had no adverse childhood experiences.

Trauma, abuse, and addiction has run through generations of my family. Yet I don’t blame my family, or their parents, or their parents’ parents. It’s the hand that I’ve been dealt, but it doesn’t mean that I have to fold. To pull from Randy Pausch’s words in The Last Lecture, I can’t change the cards I’ve been dealt, but I can change how I play my hand.

The will to change

Codependency, narcissism, patriarchy, christian nationalism, white supremacy. These were the systems I grew up in. For years, I thought if I just refused and resisted these systems, that I’d be impervious to them, and that my actions and thoughts would be guided by my resistance. Yes, I may have watched a little too much Star Wars, and had a rosy outlook of it all.

But to play off the words of Dr. Bruce Perry and Oprah in What Happened To You, I can’t give what I didn’t receive. And I couldn’t just think and behave from a place of love, connection, trust, worth, confidence, and freedom when that’s not what was modeled to me. The majority—95%—of our development happens by the time we’re six years old. Some of the worst, most traumatic experiences that I can remember, were around the age of five and six. And I can’t just ignore that and assume that the abuse, neglect, and unhealthy systems that were modeled to me wouldn’t affect me.

“Recovery from codependence is a lot like a growing up process - we must learn to do the things our dysfunctional parents did not teach us to do: appropriately esteem ourselves, set functional boundaries, be aware of and acknowledge our reality, take care of our adult needs and wants, and experience our reality moderately.”

― Pia Mellody, Facing Codependence: What It Is, Where It Comes from, How It Sabotages Our Lives

One of the hardest realizations of the last couple of years has been learning that so much of my adult life has been a response to my childhood. That was a helluva horse pill to swallow as I started to realize that even many of the most important things of my life were in part reactions and responses to my childhood. Last year then became like this personal journey back to my childhood, and through generations of my family, to recall, learn from, and let go of the memories, experiences, and systems that had had such a profound effect on me.

It was like an opening of Pandora’s Box. I had to recall the physical abuse. I had to write about the adverse experiences. I had to talk to a therapist about the trauma. I had to go through the family records and news clippings. I had to ask the hard questions to family members. And I even returned to my childhood hometown for the first time in a decade. It was like returning to the scene of the crime. And I so expected that it would flood me with traumatic memories and surface such negative emotions. It did the opposite, however, as I was flooded with so many positive memories that I’d long ago buried.

One of the most important parts of that trip were returning to some of the places of my worst memories. There was no anger, blame, or resentment. Rather, I felt these immense feelings of pride, forgiveness, and freedom sweep over me, as I said, “You no longer have power here.”

For much of my life, however, there was a lot from my childhood that deep down I was angry, resentful, and bitter about. Yet I kept it all buried, and therefore kept connection to myself and others at arm’s length. There were a lot of ways of coping with those things, and coping with life, which were ultimately just perpetuating the systems I grew up in. I was never completely over-my-head addicted to one thing. But there were all these different things I used as coping mechanisms, and that I was giving my power away to like travel, relationships, porn, alcohol, weed, and food.

The most telling proof of how I was perpetuating systems was in how I handled relational conflict, like rejection, break-ups, or anxieties I was having about a relationship or potential relationship. Rather than have conversations, or be with the feelings I was experiencing, I would take very spontaneous trips. Once, after seeing an ex at an event, who I felt resentment toward for how she treated me, I got on the highway to drive to New England (I lived in L.A.). A few miles in I turned around.

But I didn’t just randomly start traveling whenever life and relationships got messy. It was what was modeled to me. One of my caregivers would typically storm out of the house after conflict, and we wouldn’t see them for days, usually with no contact. I vividly remember one of them as a kid, watching my other caregiver cry on the phone with police, as their partner had stormed out of the house angrier than we’d ever seen, and they’d taken their hand gun with them.

Travel, love, sex, alcohol, weed, and food aren’t bad in and of themselves. Yet I was using those things to self-soothe because I never learned what it feels like and looks like to be connected with myself, know my worth, and be grounded. I looked for connection, love, and worth outside of myself. It’s what was modeled to me. Little by little, travel, love, sex, coffee, alcohol, and food were these things that helped me feel hits of aliveness, while continuing to perpetuate the disconnection I felt to myself and others.

So two years ago, after starting to lean more into my emotions in 2019 and 2020, I really dove into discovering what it meant to be grounded, connected, worthy, and in touch with myself. To play off Pia Mellody’s quote above, I had to learn to do the things which should’ve been taught and modeled to me in childhood, but which I had to start doing for myself as a 40-year-old. It’s like I had to create a new baseline. It brought everything into question, including my relationship with things like coffee, travel, alcohol, my career, and love. Just about everything was put on the chopping block.

“In patriarchal culture males are not allowed simply to be who they are and to glory in their unique identity. Their value is always determined by what they do. In an antipatriarchal culture males do not have to prove their value and worth. They know from birth that simply being gives them value, the right to be cherished and loved.” ― bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

What changed when I became sober

There’s a lot that hasn’t changed. I still go out to bars, for example, especially right now during the WNBA and baseball playoffs. When I take myself on a solo restaurant date, I still sit at the bar. And there are few things that are a better conversation starter at a bar than ordering a non-alcoholic beer—and especially when I’m sitting there journaling. On one of these nights, last winter, a bartender at a local beer bar asked me if I felt better after I stopped drinking. And before I could even reply, she says, “You feel better, don’t you?” I thought about what I wanted to say and took a sip of my drink, but again, before I could answer, she continues, “You feel better—of course you feel better, you’re not putting alcohol into your system.”

I felt like that encounter was quite telling about where we are as a society on the subject of alcohol. Dr. Sanjay Gupta, in a recent CNN segment, citing a study by NCSolutions, stated that 61% of Gen Zers are willing to cut back on drinking, or not drink at all. That same study mentions that 41% of Americans are drinking less. Major booze and beer brands must be losing their shit at stats like that. Or, they're getting with the program, like Guinness and Heineken, who are making their own non-alcoholic drinks. And many of them are pretty damn good (not sponsored).

NCSolutions’ study states that 36% of Gen Zers are going alcohol-free because of mental health, which I would say was my no. 1 reason for quitting. This is reflected in conversations I’ve had recently, as well as books I’ve been reading, like The Unexpected Joy of Being Sober by Catherine Gray. Gray writes that the penny started to drop when she began noticing that her suicidal thoughts disappeared almost immediately when she started trying to get sober.

Here’s my unpopular science knowledge drop: There is no amount of alcohol that is good for us. I feel like societally, we hang onto the words of articles like the ones I mentioned at the start, and especially when their headlines read something like "I'm 100 years old and the secret to a long life is drinking gin." I would often share them on social media, with a clever (or so I thought) quip about how drinking whiskey was “good for you.”

Yes, there are studies that have linked red wine with longevity and the lowering of heart disease, as this Wine Enthusiast article points out. And Dan Buettner, in his fantastic cookbook, The Blue Zones Kitchen, notes that in certain parts of the world, like Sardinia, with one of the highest life expectancies, the culture incorporates wine into their lifestyle and diet. I’m not going to deny that there are some very healthy groups of people and communities, where alcohol in moderate doses, is a part of their lifestyles. But generally speaking, the science isn’t good for booze.

This UCHealth article briefly explores how light to moderate alcohol consumption came to be considered “good for you.” This belief is largely attributed to a 1997 study of nearly 500,000 people who were tracked over the course of 9 years. The study found that "men and women who had had at least a drink a day had 40% and 30% lower risk of cardiovascular disease than those who didn’t drink — and that overall death rates were lowest among men and women reporting about one drink daily." Like all studies, it had its limitation, and didn't account for a variety of factors like diets, how physically active they were, medical access, and overall health.

As the UCHealth article continues, more recent studies, like this one, have found “no protective effect” from alcohol consumption, and what’s more, they’ve found elevated health risks. Alcohol after all has long been classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), alongside tobacco, asbestos, gamma-radiation, and other risks. The World Health Organization meanwhile published a statement, in 2023, which read that "there is no safe amount that does not affect health.” Risks start from the first drop, the statement reads.

But listen, we’re at risk of something every time we leave the house, and even without leaving our house. So I’m not here to judge, persuade anyone, or provide medical advice. Not a doctor. Nevertheless, this was all a part of my personal research and considerations as I was thinking about whether my break from alcohol would be just that, a break, or whether it would be a lifestyle change.

One of the things I became increasingly uncomfortable with was the system and culture of drinking, especially in America. It was a system and culture that I perpetuated. I remember several years ago, ordering a drink at one of the preeminent hotel cocktail bars in Las Vegas, when the bartender told my friend and I that he didn’t drink. I was befuddled. How could someone, who’s job it was to make delicious drinks, not drink?

Boy, did I have my judgy pants on high and tight. But oh how the tables were flipped this last year and a half, when I, the guy who’s spent years making and photographing cocktails, felt like I was having to justify why I was ordering a non-alcoholic beer or mocktail.

When I quit drinking coffee and alcohol, it was kind of like I’d all of a sudden moved to a country where I didn’t know the language and customs of the culture. It’s like the blinders fell off when I experienced firsthand how much my life and the world runs on caffeine and alcohol. I’ve spent what’s felt like an eternity scrolling through restaurant and bar menu photos on Yelp, and zooming in to see if I could find at least one non-alcoholic drink. There were times when I completely walked out of bars and cafes when there was nothing for me to drink other than water. Yet other times I experienced a lot of kindness and grace from bartenders and service professionals, and had such meaningful conversations.

How lucky am I to live in this moment in time when there are so many different non-alcoholic options. I’ve tried the non-alcoholic beers of nearly 50 different brands in the last year and a half. 50! And I’ve tried about that many non-alcoholic wines and spirits.

For the most part I feel overwhelmingly grateful. I’m fortunate that I can stroll into a restaurant or cocktail lounge, and comfortably sit at the bar and confidently order a non-alcoholic drink. I’ll see one of my favorite tequilas or whiskeys on the shelf, and reminisce about an evening that I enjoyed a glass of it while in conversation with a friend. But I haven’t felt an urge to order a glass of whiskey or tequila. There are many people who can’t walk into a bar or even be near alcohol. Addiction is real, and I hurt for those who have absolutely been through it on their road to recovery.

If I had to distill everything I’ve learned the last 18-24 months to one thing that stands above all the other change, growth, and evolution, it would be this: A momentous shift in where I draw my worth, connection, joy, and love from. When I look at my life two years ago, and where I drew on worth, connection, joy, love, value, power, freedom, and confidence from, it was completely differently then were I draw on those things today. And the day it really started was the day I admitted to myself that I was codependent.

What was modeled to me early on—from culture, my parents, my environment, school, norms, etc.—was that whatever I may not be feeling and wanting from inside of me, must be found outside of me. It is like bedrock of American culture and patriarchy. If I wanted to be seen, loved, heard, valued, happy, soothed, etc., then I had to find that outside of myself.

“Learning to wear a mask (that word already embedded in the term “masculinity”) is the first lesson in patriarchal masculinity that a boy learns. He learns that his core feelings cannot be expressed if they do not conform to the acceptable behaviors sexism defines as male. Asked to give up the true self in order to realize the patriarchal ideal, boys learn self-betrayal early and are rewarded for these acts of soul murder.” ― bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

I witnessed this firsthand every time I was dropped off at the barbershop so my caregiver could go in the back to look at porn, and every time they left to travel for days at a time when there was conflict. I saw it from another caregiver who got their worth from codependency. I saw it in the way friends abused substances. And it was like the source code of the masculinity that was modeled to me.

And at the tail end of my thirties I was fucking exhausted. That conversation with my therapist was the kick in my pants to finally put to rest so many of the systems, which were lauded as benefitting me the most as a white, straight, cisgender man, but were calamitous to my body, my mental health, my relationships, my work, and the world.

I may have not been addicted to alcohol or other things in the traditional sense of the term. But make no mistake about it, my work was recovery. I get emotional every time I read or listen to what Glennon Doyle says in episode 199 of We Can Do Hard Things in regards to her recovery when she talks about figuratively throwing herself off the cliff:

“I’m going to throw myself off the cliff and just assume that the person I’m going to become after is going to be at the bottom of the cliff and is going to catch me. And that there’s a bunch of shit that’s going to happen in that fall that’s going to change me into a different woman by the time I catch myself at the bottom. And so, you trust that. I don’t even know if it’s trust, it is this ridiculous hunch.” — Glennon Doyle

And I did catch myself. And a lot of the moments between jumping and catching myself were so stupid. There wasn’t just one addiction that I was quitting, but all these learned behaviors, thoughts, and activities—codependent relationships, drinking, coffee, travel, hustle work culture, porn—that I largely quit over a relatively short period of time. The other side of quitting those things is less a 40-yard dash and more of an ultramarathon—all uphill. Have I convinced you yet of the virtues of recovery?

Yes, I’ve experienced a lot of physical and mental benefits, like decreased inflammation, better sleep, greater clarity, less sluggishness, and better energy, to name a few. But when I really look at my life the last year and a half, I see a life that is more grounded, connected, open, curious, and zen. There are moments when part of me misses that life I had when I only felt a handful of emotions, and coped by booking a spontaneous international trip or by going on a bar crawl. But this work of recovery and healing, while being some of the hardest work of my life, I’d do over and over again for the rest of my life.

I want to end this section with this great quote from one of the books I read this year, Dopamine Nation.

“I urge you to find a way to immerse yourself fully in the life that you’ve been given. To stop running from whatever you’re trying to escape, and instead to stop, and turn, and face whatever it is. Then I dare you to walk toward it. In this way, the world may reveal itself to you as something magical and awe-inspiring that does not require escape. Instead, the world may become something worth paying attention to. The rewards of finding and maintaining balance are neither immediate nor permanent. They require patience and maintenance. We must be willing to move forward despite being uncertain of what lies ahead. We must have faith that actions today that seem to have no impact in the present moment are in fact accumulating in a positive direction, which will be revealed to us only at some unknown time in the future. Healthy practices happen day by day. My patient Maria said to me, “Recovery is like that scene in Harry Potter when Dumbledore walks down a darkened alley lighting lampposts along the way. Only when he gets to the end of the alley and stops to look back does he see the whole alley illuminated, the light of his progress.”― Anna Lembke, Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence

What I’m learning about addiction

I’ve been reading a number of different addiction memoirs and stories recently, and reading Gabor Maté’s fantastic book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. If you’re not familiar with Gabor Maté, he’s a Canadian physician, who in recent years has become an expert on childhood development, trauma, and addiction. His work on addiction, and his book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, is the result of working on Vancouver’s Downtown East Side with patients challenged by addiction and mental illness. Gabor, in my opinion, and the opinion of many others, is one of the foremost living voices on trauma.

I wanted to read this book because for one, it’s been widely recommended and lauded. But more importantly, I wanted to understand the science and brass tacks of addiction. Because I have some strong opinions and hot takes on addiction, and the way, particularly in America, that we’ve criminalized addiction and substance abuse, especially with America’s “war on drugs.” I call bull shit.

Among my biggest problems is how we’ve criminalized and dehumanized drug use. From the outset of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Gabor makes a strong case that there is no “war on drugs.” As Gabor writes, “One cannot make war on inanimate objects, only on human beings.” As Gabor continues, “And the people the war is mostly waged upon are those who have been the most neglected and oppressed in childhood, for, according to all the science, all the epidemiological data, all the experience, they are the most likely to succumb to substance addiction later in life.”

Famous trauma researcher and author Dr. Bessel van der Kolk is quoted by Gabor as saying, “We need to talk about what drives people to take drugs.” It’s people who have experienced pain and don’t feel good about themselves who are most likely to take drugs. As Dr. Bessel writes in The Body Keeps the Score, “But if no one has ever looked at you with loving eyes or broken out in a smile when she sees you; if no one has rushed to help you (but instead said, “Stop crying, or I’ll give you something to cry about”), then you need to discover other ways of taking care of yourself. You are likely to experiment with anything—drugs, alcohol, binge eating, or cutting—that offers some kind of relief.”

As Gabor writes, his mantra and first question isn’t, why the addiction? Rather, it’s why the pain? This looks not at the behavior but rather the pain and trauma. Yet at least in America, healthcare providers historically aren’t even trained in trauma. When Gabor graduated from medical school, he hadn’t heard a single mention of psychological trauma and its impact on human health in his training. Gabor references numerous other doctors who received absolutely no training on trauma.

In America we criminalize addiction. Gabor cites in his book a stat that Americans make up 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of the world’s prison population. That discrepancy, in part, is because of what Gabor describes as an “antiquated social and legal approach to addiction.”

The reason why this has been important for me to read is because that I know without a shadow of a doubt that the culture I grew up in, my childhood abuse, and the systems that were modeled to me, predisposed me to addiction. Hard stop. As I mentioned before, my Adverse Childhood Experiences score is between 4-5. That means that I’m nearly 7.5x times more likely to become addicted to alcohol. And truthfully I did become addicted, though it was more of a cocktail of addiction to travel, love, porn, and more of these “praise” addictions, rather than substances.

Gabor uses a 2001 definition of addiction, defining it as a “chronic neurobiological disease characterized by behaviors that included one or more of the following: Impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.” One of the things that he points out about addiction is that a lot of people liken addiction to the “quantity” of drugs or alcohol, when it’s far less the quantity and far more the impact that characterizes addiction. Today, addiction has come to be understood as a brain disease, because as Gabor writes, “all addictions share the same brain circuits and brain chemicals.”

Gabor, however, urges caution when thinking about addiction like a medical disease because of all the “biological, chemical, neurological, psychological, emotional, social, political, economic, and spiritual underpinnings.” Because here’s the thing, despite what many of us have heard, drugs themselves aren’t the root cause of addiction.

For many years it was generally believed that addiction was caused by substance's addictive properties. This was largely because of lab studies in which rats were isolated in small cages, and when given the option between water and self-administered drug-laced water, the rats kept coming back to the drug-laced water and eventually died. It was actually part of a big anti-drug campaign in the 1980s. And yes, there was a commercial.

But in the 1970s psychologist Bruce Alexander started to question the validity of these types of experiments, especially when you removed animals from the wild, put them in a confined space under stress, and isolated them from others. So he built a “rat park,” with two different groups of rats, one that had been in confinement and the other group from a rat colony. Both had been given levels of morphine. When they were both put into this rat park, and given the option of water and morphine, the rat colony group drank significantly less morphine than the group of rats that had been under stress and isolated from other rats.

Okay, you may be thinking that that’s rats, but what about humans? Well around the same time, there was another, more organic experiment going on, called the Vietnam War. And it's believed, with evidence to back it up, that about 20 percent of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam had become addicted to heroin, according to a study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. There was immense concern that all of those U.S. soldiers would return addicted. However, according to that same study, about 95% of those addicted soldiers stopped using after returning from the war. You can read more about this here in Greater Good Magazine.

This is important for so many reasons. One, it flies in the face of so much of the “war on drugs” narrative. I believe it also challenges many of the assumptions about addiction and addicts. Color me not shocked that isolation, disconnection, trauma, and stress would lead to addiction. This explains in part why many times, after stopping one addiction, an individual will replace it with another addiction. This is known as addiction replacement.

“We see that substance addictions are only one specific form of blind attachment to harmful ways of being, yet we condemn the addict's stubborn refusal to give up something deleterious to his life or to the life of others. Why do we despise, ostracize and punish the drug addict, when as a social collective, we share the same blindness and engage in the same rationalizations?”― Gabor Maté, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction

What’s most sad and frustrating to me is the science and data about substance abuse among people of color and indigenous groups. The American Addiction Centers discusses that while Native Americans make up less than 2% of the U.S. population, the rates of substance abuse and dependence is higher in Native Americans than any other group. Native Americans also have the highest rates of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalant, and hallucinogen use disorders in comparison to other ethnic groups. The 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 1 in 5 Native American young adults (aged 18-25 years) has a substance use disorder.

Another report, from the CDC, shows the stark increase in overdoses in recent years among Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people. In 2020 overdose death rates increased by 44% for Black people and 39% for AI/AN people, according to a new CDC Vital Signs report with drug overdose data from 25 states and the District of Columbia.

Another report studied how the pandemic disproportionately worsened a wide range of outcomes for minorities. Dr. Helena Hansen, a co-author of the report says in this NPR article, "People who are lower down on the social hierarchy tend to be exposed to fentanyl and other highly potent synthetic opioids at disproportionate rates." As she continues, "You find Black Americans are exposed to fentanyl more often than white Americans."

This is heartbreaking. I admit that it doesn’t paint a complete picture, yet so much of the science points to the connection between trauma and addiction. And people of color and indigenous groups have long experienced immense trauma at the hand of white oppressors. To address substance abuse and addiction I believe that we culturally must acknowledge and address the trauma that’s caused much of it, our systems that perpetuate it, and the language we use that continues to stigmatize it. We must do better.

“We’re all running from pain. Some of us take pills. Some of us couch surf while binge-watching Netflix. Some of us read romance novels. We’ll do almost anything to distract ourselves from ourselves. Yet all this trying to insulate ourselves from pain seems only to have made our pain worse.” ― Anna Lembke, Dopamine Nation

Hot take coming in hot. We are all addicts. The sooner that I was able to accept that, the sooner I was able to heal and live more meaningfully. My frustration is that we as a culture criminalize and dehumanize addictions like drugs in particular, all while we societally indulge in and perpetuate many other addictions.

For example, in episode 288 of Glennon Doyle’s We Can Do Hard Things podcast, Alanis Morissette describes “praised addictions,” like work. The pandemic changed the workplace, and how people work. And many companies, and even countries, have reimagined work. Countries like Portugal and the UK have experimented with 4-day workweeks, while Belgium was the first country to legislate for a 4-day workweek (though it didn’t reduce hours like other countries and companies have done). Even Japan, which is considered such a workaholic country, is considering a 4-day workweek. However, in some sectors, the stress and negative impacts are ever-present.

There have been conversations about this, particularly in the financial industry, where J.P. Morgan recently capped work hours at 80 hours per week, after a 35-year-old investment banker died following 100-plus hour work weeks (read more about it here). Even an 80-hour week is unconscionable to me, but at least it’s moving in the right direction? It seems fitting to be writing about this following the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Day, especially since the theme was on mental health in the workplace.

While work addiction isn’t a formal diagnosis, research would suggest that it may be more common than people may think, especially in cultures and workplaces where performance is such a measure of success. This article from The Conversation discusses how many of the negative impacts of addictions like drug and alcohol addiction are prevalent in work addiction. This includes depression, decreased mental health, and stress.

A Psychology Today article, featuring a comprehensive literature review using US data, estimated the prevalence of work addiction among Americans at 10%. Some estimates are as high as 25%, through as the author mentions, that may be related to "excessive and committed working" rather than addictive behavior.

Beyond work addiction, there are other addictions, like love addiction, which not long ago, there was little to no research on. Another Psychology Today article summarizes some of the research on the prevalence of love addiction. Love addiction has been found to be as high as 10%, through much higher in certain populations like college students.

One of the biggest conversations about addiction in recent years has been that of Internet or social media addiction. California State University reports an estimated 10% or 33.19 million Americans are addicted to social media, according to addictionhelp.com. The Surgeon General made waves last year when they issued an advisory about social media’s impact on youth health.

Simply put, addiction goes far beyond just drugs and alcohol. Hell, even travel, and more specifically, dromomania, was added years ago for a period to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is basically psychiatry’s bible. It’s complex, and it’s not something we can just put into a box or treat with dehumanization, criminalization, and prison sentences.

“Not the world, not what’s outside of us, but what we hold inside traps us. We may not be responsible for the world that created our minds, but we can take responsibility for the mind with which we create our world.”

― Gabor Maté, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts

One of my favorite psychologists, thought leaders, and voices on this is Vanessa Bennett, who I’ve frequently quoted here. And as she often says, "one person's Jack and Coke is another person's people pleasing." As she continued in this Instagram post, "Addictions all serve the same purpose, regardless of what they are. They are a way to self soothe, to not feel shame or discomfort, a way to hide and numb - they are a coping skill we reach for when we have not developed other healthier ways."

Damn, I really brought the room down didn’t I? BUT, I strongly believe that there is hope. And I say all this not to judge, not to overtherapize, and not to shame anyone into admitting addictions that they may or may not have. But I do believe in the power of radical vulnerability, recovery, and running toward our challenges and our pain rather than away from them. Life opened up far more profoundly, and I experienced such exponential growth, when I was radically honest with myself.

It started with turning the mirror around on myself, as Vanessa encourages in that Instagram post I linked to above. Because when I did turn the mirror on myself, I didn’t just start to see myself with so much more empathy and compassion, but I started to see everyone else, and especially people struggling with addiction, with so much more empathy. Because we’re all in grief. We are all grieving something.

In his book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Gabor Maté, who’d spent a decade treating addicts at the Downtown Eastside Vancouver clinic, reflects about attending his first AA meeting after acknowledging his own addiction. He writes, “What I’ve witnessed here are humility, gratitude, commitment, acceptance, support, and authenticity. He continues, “I so desperately want those qualities for myself.” Glennon Doyle calls invitations into recovery “some kind of cosmic honor.” While it doesn’t feel like it in the moment, the initial acceptance and letting go is where the magic starts to happen.

“I urge you to find a way to immerse yourself fully in the life that you’ve been given. To stop running from whatever you’re trying to escape, and instead to stop, and turn, and face whatever it is. Then I dare you to walk toward it. In this way, the world may reveal itself to you as something magical and awe-inspiring that does not require escape. Instead, the world may become something worth paying attention to.”

― Anna Lembke, Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence

Later in his book Gabor writes, “In choosing sobriety we’re not so much avoiding something harmful as envisioning ourselves living the life we value. As he continues, “What sobriety looks like will vary from person to person, but in all cases it has the individual, rather than the addictive compulsion, in the lead.” There’s great power in that. As addiction begins and ends with us, so does healing begin and end with us.

We live in a society where addiction and talking vulnerably about addictions and struggles is often considered shameful and a weakness. But lo, there is nothing more courageous. To quote Brené Brown from The Gifts of Imperfections, "Embracing our vulnerabilities is risky but not nearly as dangerous as giving up on love and belonging and joy—the experiences that make us the most vulnerable. Only when we are brave enough to explore the darkness will we discover the infinite power of our light.”

I can only hope that as we turn the mirror on ourselves, acknowledge and address our pain, and have more conversations like this, we’ll heal ourselves. In turn, it’ll be like a superpower for others, and result in collective healing.

“It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.” —Theodore Roosevelt, Speech at the Sorbonne, Paris, April 23, 1910

For your next dinner party

Whew, is it just me, or these essays getting longer? Don’t answer that. I’ve mentioned a LOT of books and resources. I’ve included a few below. If you have just 15 minutes, I highly recommend Johann Hari’s fantastic TED talk from 2015. Some of the stories I mentioned here, and that Gabor Maté discusses in his book, are referenced by Johann.

There are SO many articles, books, videos, podcasts, studies, TikToks, and all the things about sobriety, recovery, and addiction. Below are a few of my faves. Not all of them I’ve finished reading, but these are some of the standouts.

I’ve said this before, and I mean it now more than ever, but don’t hesitate to reach out, whether you disagree with me, want to admit your own struggles, have questions, or just want a good non-alcoholic drink recommendation. For the latter, you can find my short list at the end of my first essay about sobriety.